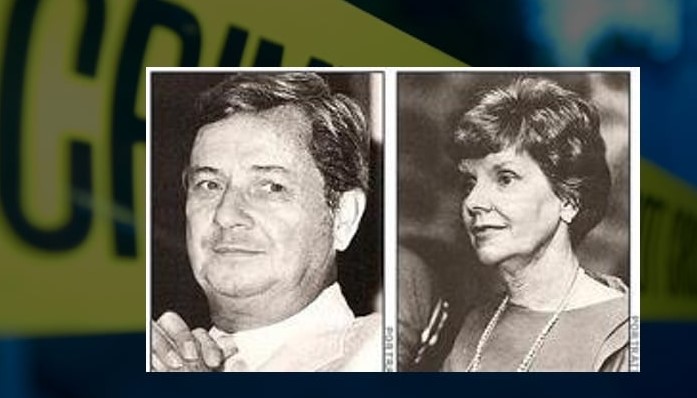

How the Dixie Mafia’s Lonely-Hearts Money Scam Led to the Murder of Circuit Court Judge Vincent Sherry and his wife, former Councilman Margaret Sherry.

Judge Sherry and his wife, Margaret, were found dead in their home in a quiet north Biloxi neighborhood on September 16, 1987. They had been shot multiple times, point-blank in the head.

But nobody knew Vincent and Margaret, both 58, lay dead in their home.

They were supposed to be out of state visiting with their daughter, so no one realized anything was wrong until two days later when the Judge failed to show up in court on Wednesday, September 16.

Calls to their home were unanswered. His colleagues at the court phoned Pete Halat, Vincent Sherry’s friend and former law partner. But he hadn’t seen or heard from the Judge either.

Pete Halat left a concerned message on Sherry’s answering machine. He then felt he had better check on his friend. On his way out, he asked his Junior Partner, Charles Leger, to ride with him.

Upon arriving, they noticed that both cars were still in the driveway. Halat asked Leger to go to the house while he asked the neighbor if she had seen the couple. She hadn’t seen them for a couple of days, which she thought was odd since their cars were in the driveway.

Leger rang the doorbell, but no one answered. He saw the last two morning newspapers were still outside the house.

When Leger tried opening the front door, he found it unlocked. Something wasn’t right. He yelled to Halat. Pete Halat cautiously stepped inside. A few steps in, he made the gruesome discovery. Judge Sherry had been gunned down in his own home.

When Pete Halat (also neighbor and friend), discovered the body, the Circuit Court Judge’s corpse was slumped in the den. Police would later find the body of Margaret Sherry, who aspired to be Mayor, in the bedroom. There was no sign of forced entry to the house.

When Halat gave his first statement to investigators, he told them that immediately after seeing Vince lying dead on the floor, he retreated out of the house without looking further. “I had no idea that Mrs. Sherry was in the house,” he told crime scene investigators.

However, according to Leger, he remembered that Halat had walked into the Sherry’s living room, seen Judge Sherry’s body, and said, “Vince and Margaret are dead.” Halat ushered him outside quickly. However, Margaret’s body was in the far back bedroom. According to Leger, Pete briefly entered the front of the house and would have no way of knowing that Margaret was in the rear bedroom of the residence. How could Pete Halat have known that Margaret was dead if he hadn’t gone into the bedroom and seen her body?

The double murders of two prominent citizens stunned the city of Biloxi, Mississippi. The revelations to come would prove even more shocking. (SunHerald)

Murder Mystery

The execution-like manner of their murder and the lack of any signs of a break-in led police to think it was a gangland hit. Several promising leads led the authorities to mob figures who refused to talk.

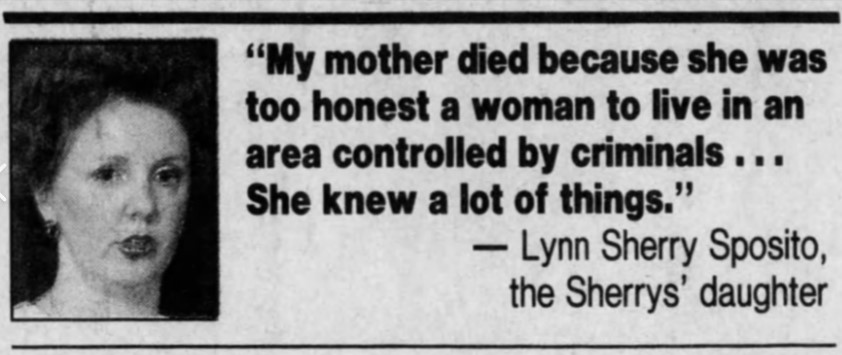

The local police investigated the murders for two years but didn’t get anywhere. The case soon went cold. However, the Sherry’s daughter, Lynne continued pursuing the investigation on her own, receiving death threats in the process and arming herself against the likelihood of any of them being carried out. A friendly FBI agent in Jackson suggested that she hire a private detective, and that’s what she did.

In 1989, the Sherry’s children hired Rex Armistead to help them find the killers. Armistead was a Private Investigator who’d also been a Highway Patrol Officer and had helped put several members of the Dixie Mafia in prison already. He had a reputation for getting the job done.

Two prominent citizens were found dead, leading to a trail of conspiracy on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. It looked like a professional hit, and the local police investigation went nowhere.

It would take years to break the conspiracy of silence and untangle the corruption.

September 14: The Double Murder of Margaret & Vincent Sherry

It was a typically warm summer night. The workday was over, and most residents had retreated to the tranquility of their homes. Like most neighbors, the Sherrys were unwinding after a long day. Vincent Sherry was a prominent judge, and Margaret Sherry was planning to run for Mayor.

Both were fixtures of Biloxi’s social community functions. They were a happy couple who had raised three grown children. The next day, they had planned to visit their out-of-state daughter. Their life together seemed ideal.

They were settling in for the night when an unexpected visitor came to the door and brought their perfect world to an end.

Two days later, their bodies would be discovered. The Biloxi Police arrived to find Vincent Sherry’s body at the front of the house. In the back bedroom, they discovered Margaret. The investigation became a top priority.

The Police Officers contacted the Biloxi’s FBI Field Office for additional resources.

Inside, the police began examining the crime scene and collecting evidence. There was no forced entry, no items were stolen, there was no struggle,

The killer had covered his tracks well. Nothing found at the scene pointed to the shooter’s identity. His mission was clear: The Murderer came there for one thing—to kill Vincent and Margaret.

FBI Agent Bell agreed that this was a professional job. The couple had been assassinated. It was well-planned, well-executed, and professionally done.

A multi-agency task force was assembled. Investigators spent days processing the crime scene.

They grappled with a single question: Why had Margaret and Vince Sherry been murdered?

Investigators thought Judge Sherry could’ve been murdered anytime while taking his morning jogs around the neighborhood. So, why kill Margaret Sherry?

Investigators believed it might have to do with the controversy over Biloxi’s future to transform it into a flashy resort where casinos would attract tourist dollars. But with strip clubs already established in town, Margaret thought the small-town charm would be threatened. As a candidate for Mayor, she had made powerful political enemies by trying to keep gambling out.

FBI Agent Bell wondered if Margaret was killed to silence her protest. She was anti-gambling, and if elected Mayor in 1989, she had planned to close down the remaining strip clubs. So, it was unclear whether Margaret or Vincent was the prime target.

Even people in the neighborhood who were friends of the couple were reluctant to talk, fearing Biloxi’s criminal underworld. Many citizens hesitated to be interviewed by agents or police officers because they did not want their names tied to anything concerning this case.

Lynne, the Sherry’s daughter, was determined to find justice. She questioned everyone in the neighborhood. One family friend gave her a crucial piece of information. He described a suspicious car and driver in the neighborhood on the night of the murders. She took the lead to the local police. He identified a Ford Fairmont driving in front of the Sherry’s home on Monday night, Sept. 14. The police began a search for the car.

A few days later, they found an abandoned car matching the witness’s description. It was a Ford Fairmont. It had been reported stolen one day before the murders. The tag on the car was from a stolen vehicle three years earlier. Following the story of the stolen tag might lead to the killer. This vehicle was likely the killer’s getaway car. They examined it, hoping to find the killer’s identity. They discovered that the last person to be seen by the car was a locksmith. Lenny Swetman belonged to a loosely organized group of criminals that the FBI was investigating in another case. The group was known as the Dixie Mafia.

Now, FBI Agent Bell wondered if the Dixie Mafia was linked to the Sherry murders. He began looking into Swetman’s associates. If Swetman had a part of it, other Dixie Mafia members couldn’t be far behind. What that meant was if Swetman was involved in getting the tag for the hit car, then quite likely his close personal friend and long-time associate, Mike Gillich, strip club owner, might also be involved in these murders.

Gillich owned three strip clubs in Biloxi and was well known to local law enforcement. He had been under investigation by the FBI in connection with the Dixie Mafia operation, known as the Lonely Hearts scam. But they needed to connect the two investigations.

The Lonely Hearts Money Scam

Dixie Mafia inmates at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola were behind a scam that brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars. Ringleader Kirksey McCord Nix—a convicted murderer serving a life sentence without parole—believed that if he raised enough money, he could buy his way out of jail.

Here’s how the scam worked: Inmates paid guards to use prison telephones. Then, they placed bogus ads in homosexual publications claiming they were gay and looking for a new partner to move in with. The men who replied to the return post office box address got additional correspondence and racy pictures. But there was a catch—the scammers told their victims various lies about why they needed money before they could leave where they were.

“A lot of money came flowing in,” said retired Special Agent Keith Bell. “There were hundreds of victims.” Men from all walks of life—professors, mail carriers, politicians—fell victim to the scam. “One guy in Kansas mortgaged his house and sent $30,000 to the scammers over a period of months,” Bell recalled.

To add insult to injury, some of the inmates writing letters eventually confessed the scam to their victims—and then extorted even more money by threatening to “out” the men if their demands were not met. The Dixie Mafia Lonely Hearts Scam

FBI Agent Bell’s Investigation

Agent Bell began investigating. It was run out of the Angola prison in Louisiana by Kirksey Nix, the incarcerated kingpin of the Dixie Mafia. Nix would run ads in gay magazines asking for money to help fictional gay men get out of trouble with the law. Through the scam, Nix hoped to generate enough money to solve his legal problems. He was serving a life sentence for murder.

From his jail cell, Nix coordinated the homosexual scam, which generated hundreds of thousands of dollars from individuals around the country, including Canada. With this money, he intended to buy his way out or attempt to buy his way out of his prison sentence. Believing they were helping men in prison, they would wire or mail money to a nearby Western Union. Nix would then call his contact on the outside, Mike Gillich. Gillich would then dispatch his bag man to retrieve the money.

Gillich ensured the scam money was distributed to the mafia members and carefully stashed away for Nix.

A year into the FBI’s investigation, the murder case had stalled.

The Private Investigator

After 16 months, the Sherry’s daughter, Lynne, grew increasingly frustrated. In January 1989, she hired a private investigator to rev up the inquest into her parent’s murder. The family had wanted a quick resolution to the case, but there were still no arrests. At this time, the FBI had not formally entered the case. They were only assisting the local police.

The private investigator met with FBI Agent Bell to discuss the details of the case. The private investigator began following up on leads. He would interview an inmate at the Angola prison to try to link the Lonely Heart Scam to the murders. He met with Bobby Joe Fabian, a known member of the Dixie Mafia, doing time for kidnapping. Fabian claimed he had not been involved in the Sherry murders, but he had learned that fellow inmate Kirksey Nix had been.

Fabian told the PI that Nix had Vincent Sherry killed because he had allegedly stolen money from Nix’s Lonely Heart scam. He also said Nix had been informed of the theft by Pete Halat, Sherry’s former law partner. Halat, the man who had delivered the eulogy at the Sherry’s funeral, was now implicated in their murders.

Pete Halat officially represented Nix on legal matters, but Fabian said Halat’s role with the Lonely Hearts scam was criminal, not legal. Halat was one of the people receiving money from Nix for safekeeping. The ties between the outlaws and the lawyer went deep.

Nix planned to pay for a pardon, either from the parole board or from then-Governor Edwin Edwards.

Kirksey Nix’s girlfriend, Sheri LaRa Sharpe, worked in Halat’s office. Fabian said LaRa and Pete Halat were stashing money from the scam in a safe deposit box for Kirksey Nix. He said the amount had reached six figures.

Thanks to Fabian, the link between the murders and the Lonely Hearts scam was established. Not only had he given a positive motive for the killings, but he also supplied the name of the alleged hitman. It was an ex-con named John Ransom, who was believed to be living in Georgia. He was a long-time alleged hitman for the Dixie Mafia.

The Official FBI Investigation

In 1989, FBI Agent Bell started investigating the murders alongside the new Biloxi Police Captain Randy Cook. They found 345 phone calls between Pete Halat’s office and the Angola prison in Louisiana. The calls ranged from December 1986 until September 15, 1987, the day after the Sherry murders. Authorities also found prison records that showed Halat had been meeting with Kirksey Nix in prison around the same time the phone calls began.

Mike Gillich was not in jail and also called for a meeting with Halat. He also profited from the Lonely Hearts scam and wanted answers. Halat again blamed Vincent Sherry

In August 1989, two years after the Sherry murders, there was enough evidence to warrant a full FBI investigation. Federal crimes involved wire fraud, mail fraud, and perhaps a hitman traveling from Georgia to Mississippi. Thus, an official FBI investigation was joined by local law enforcement.

By now, Pete Halat had been elected Mayor. With a key suspect in such a high position, investigators encountered new roadblocks. It was difficult to share information with local police officers. Mayor Halat had put his own people in as high public officials as well as the police chief.

As investigators continued to unravel the truth about the Sherry murders, Joe Fabian told his story about the Sherry murders to the TV news. He hoped that by bringing attention to himself, Kirksey Nix would be less likely to have him killed for cooperating with the authorities. The news reporters also showed a photo of John Ransom, the alleged hitman.

When Charles Leger, Halat’s junior partner, saw the photo on television, it surprised him. He recalled seeing Ransom outside the Sherry/Halat law office a few weeks before the murders. Leger shared his information with the task force. Leger remembered Ransom asking where the Sherry’s home was.

An important detail emerged from Leger. He remembered that Halat had walked into the Sherry’s living room, seen Judge Sherry’s body, and said, “Vince and Margaret are dead.”

However, Margaret’s body was in the far back bedroom. According to Leger, Pete briefly entered the front of the house and would have no way of knowing that Margaret was in the rear bedroom of the residence.

FBI Agent Bell now knew that Pete Halat was involved, but he lacked enough evidence for an arrest. Nevertheless, he confronted Mayor Halat with a quiet warning. His knowledge of the Sherry murders was much more significant than what he had shared with law enforcement authorities.

As a lawyer, Halat knew Agent Bell did not have concrete evidence to secure a conviction.

Investigators learned that Ransom was in a Georgia prison for another murder. When questioned about the Sherry murders, he refused to cooperate.

Three years had passed since the murders.

In January 1990, FBI agents went to the Atlanta Penitentiary to question another possible witness, Bill Rhodes, a known associate of John Ransom. He told them that in early 1987, Ransom had contacted him about driving the getaway car in a crime that would take place in Southern Mississippi. Ransom had said a judge would be murdered, and the pay would be $10,000. Rhodes drove to Mississippi and met with Ransom and a man named Pete. It was Pete who specifically asked Ransom to do the hit. Rhodes said he also met with Mike Gillich, who would supply the money once the hit was done. But, 5 months later, before he could do the job, Rhodes was arrested for an unrelated bank robbery, and Ransom got cold feet.

Another year would pass without much progress.

In late 1990, the investigators met with Ransom in a Georgia prison. Finally, Ransom agreed to talk. He admitted that he delivered a .22 caliber pistol to Sheri LaRa Sharpe, Kirksey Nix’s girlfriend. Ransom insisted that he did not do the job.

Ransom seemed to be a good witness. By then, he was a sick old man in a Mississippi prison missing his family. He swore he hadn’t killed Vincent or Margaret but had knowledge of the murders and would give details with the condition of immunity. He told investigators that he had refused to kill a woman, so he passed it off to another hitman, but he did provide the murder weapon with a homemade silencer.

LaRa’s involvement seems more than simply stashing money in a safe deposit box.

Through his contacts, Nix learned that the investigation was heating up. He worried that his girlfriend might talk. So, he tried to head off the problem by putting out a contract on her life. Inadvertently saving her, FBI Bell arrested her for participating in the Lonely Hearts scam.

During a polygraph test, she denied her involvement in the scam and the Sherry murders. She failed.

The FBI was ready to bring indictments against several key players.

Four were Charged: Mike Gillich, John Ransom, Nix, and Sheri LaRa Sharpe. Noticeably missing from the list was Pete Halat. The four were indicted on conspiracy to commit murder.

Questions arose as to why Pete Halat wasn’t indicted. The case against Pete Halat would have to wait for more hard evidence to arrest and prosecute the Mayor of Biloxi.

The conspiracy trial laid out the complex scheme. Gillich’s bag man helped to link the Lonely Hearts scam to the Sherry murders. However, the actual shooter had not yet been identified.

The Conspiracy Trial

On September 30, 1991, four years after the murder of Vincent and Margaret Sherry, the case finally came to trial in Hattiesburg, Mississippi right before the statute of limitations would have run out on the conspiracy charges.

The Prosecution’s Case

The prosecution focused heavily on the scams, where they had the most evidence and felt they could make their strongest case. In his opening statement, Prosecutor Peter Barrett emphasized to the jury that the case was not about trying to pinpoint the killer or killers. No one had been named in that specific role. Instead, the prosecution’s case would be to prove a conspiracy to kill the Judge and his activist wife. He cautioned the twelve jurors that there weren’t going to be any “silver bullets” or “smoking guns” in the case or any taped conversations with any of the defendants admitting guilt. Instead, he advised them to focus on the lonelyhearts scam and the role it played in the conspiracy that resulted in the Sherrys’ violent deaths.

To back their fraud charges, the prosecution had a paper trail that could have stretched from Angola to Biloxi. They had many phone records, bank documents, depositions from scam victims, and more. But, to further bolster their case, they called to stand some of the victims who told their stories about being misled and conned out of thousands of dollars. Other witnesses told the court they were couriers for the ill-gotten scam money, carrying it between Angola and other places to Biloxi where, in most cases, it was handled by Sheri LaRa Sharpe in the offices of the Halat & Sherry law firm.

The government’s final witness was another accomplice named William “Bill” Rhodes. He told the court he had been offered $30,000 by Halat and Ransom — and later by Gillich — to drive the getaway car in the Sherry hit. Even more damning to Halat, even though he hadn’t been charged with anything yet, was a statement Halat allegedly made when Rhodes had suggested sparing Margaret’s life: “No, she’s got to die. We’re under investigation, he’s the weak link. She knows his business, she’s got to go too.”

The government’s strategy appeared to be working. By establishing that the scam was bringing in large sums of money and that large sums of it had turned up missing, they established a motive for the conspiracy to commit murder-for-hire. They were also deliberately building a link to Halat that could, in the foreseeable future, lead to an indictment against him.

The Defense Counters

In their opening statements, the defense attorneys pounced on the credibility of the prosecution’s star witnesses. Nix was represented by Jim Rose, widely regarded as one of the top criminal defense attorneys on the Gulf Coast. Michael Adelman represented LaRa Sharpe, and the court-appointed Rex Jones, a former county attorney, to represent Ransom.

Defense Attorney Jim Rose postulated that the case was “a scam being run on the United States government.” He accused the government’s witnesses of “looking for something,” more specifically, a deal to reduce their sentences. He also blasted the prosecution for tarnishing the reputation of an upstanding citizen in their pursuit of their case. He wasn’t talking about his client or any other defendants; he was referring to Judge Vincent Sherry. Rose maintained that Vince’s reputation was sullied through the government’s linkage of him to the Dixie Mafia underworld.

Pete Halat’s Testimony

As the trial went into its fifth week, the unindicted conspirator, the man many felt should have been sitting at the table with the other defendants, Pete Halat, took the stand as a witness for the defense. No one on either side of the case expected him to admit to anything that could criminally link him to the defendants, but Halat did nothing to enhance his credibility while on the stand, either. He became evasive, so much so that he even frustrated defense attorneys trying to engage him in friendly examination.

Halat also made himself look suspect when he told the court he wasn’t curious about the source of Nix’s money. He maintained that had he known it was coming from illegal activities, he never would have accepted the money. He also denied ever meeting John Ransom or Bill Rhodes.

However, in matters directly related to the Sherry murders, Halat got off easy. The state never asked him about his version of his discovery of Vince’s body, how he had told Chuck Leger both Vince and Margaret were dead even though he hadn’t seen Margaret’s body at that point. He wasn’t asked about other conflicting statements he had made, either. Murder wasn’t the charge in the case, and prosecutors felt it best not to raise those issues.

Closing Arguments

The prosecution kept to the strategy they had mapped out at the beginning of the trial: to prove, by the evidence and testimony, that a conspiracy existed. A conspiracy involving considerable money, the motive for murder when that money went astray. Peter Barrett argued to the jury that, since large sums of money had been reported missing, someone would have to take the fall for crossing a dangerous man like Kirksey Nix. Neither Gillich nor Halat had wanted to take that fall, so they implicated Vince Sherry, Barrett theorized.

As for Margaret’s death, Barrett argued that it was “a bonus.” Her efforts to shut down Gillich’s operations and the very real possibility that she could become Biloxi’s next Mayor, were threats to the future plans of both Gillich and Halat, who coveted the Mayor’s office himself. Her death allowed Gillich to keep on operating his illegal activities and allowed Halat to run for Mayor without the opposition of his law partner’s wife.

And, as if in warning to the still-unindicted Halat, Barrett pointed to the defense table and said, “There is one more thing you need to remember. We take investigations one step at a time.”

Following the state’s closing arguments, the jury retired to deliberate.

The Jurors Verdict

Sequestered in Hattiesburg hotel rooms from a Thursday evening to the following Monday afternoon, the jury deliberated for 34 hours. Finally, at 3:30 p.m., Monday, November 11, 1991, the jury foreman sent a note to the bailiff guarding their privacy, announcing the conclusion of deliberations.

On the first count, the all-important conspiracy to commit fraud: “Guilty,” the court clerk announced.

On the count of wire fraud, the basis of the scam itself, guilty verdicts were read for all four defendants.

On the third count, involving interstate travel with intent to murder for hire, Nix and Gillich were convicted. Ransom was acquitted. On the fourth count, involving interstate travel by Ransom to commit murder for hire on August 8 and 9, 1987, all three of the men were acquitted. The reason for acquittal, jurors later explained when they were free to discuss the case, was that the indictment had the date wrong. The Sherry murders took place more than a month after those August dates.

LaRa Sharpe was not charged on either of the last two counts.

It would be another six months before sentencing was handed down. Defense lawyers stubbornly refused to accept the verdict and tried to delay sentencing by leveling multiple charges against the government. Finally, Judge Pickering had had enough of the delaying tactics and told the defense lawyers to prepare for sentencing in March 1992.

Halat, meanwhile, used the verdicts as further evidence of his innocence and vindication. He announced publicly that the jury did not believe the account of Bill Rhodes, who had implicated him in his statements and court testimony. However, jurors countered that they believed Rhodes and, had Halat been among the defendants, he, too, would have been convicted.

Sentencing

On March 12, 1992, all of the principals in the trial, along with spectators and the media, gathered in Judge Pickering’s court in Hattiesburg to hear the sentences.

The Judge began with LaRa. For her minor role in the conspiracy, she was sentenced to a year and a week in prison, followed by three years of probation and counseling.

Gillich received the maximum. The Judge sentenced him to three consecutive five-year terms for the three counts on which he had been found guilty, plus a $100,000 fine.

Pickering sentenced Nix to the same fifteen-year term Gillich received. Nix’s sentence was largely academic because Nix was already serving a life sentence.

Pickering gave Ransom a ten-year sentence, which would be added to the 12 years he had been sentenced in Georgia.

The verdicts in the trial were seen as a victory for the Sherry children and all who wanted justice done. It was also seen as a vindication of Margaret Sherry’s crusade to rid Biloxi of vice and corruption. Her adversary, Mike Gillich, was taken off the streets and finally made to pay for three decades of flouting the law and sullying the reputation of her adopted city, not to mention for the lives lost of those who crossed the Dixie Mafia. Three men believed responsible for Vincent and Margaret Sherry’s deaths would likely never again see freedom again. At least, that was how it seemed at the time.

But, as Nix reminded the court just before his sentencing, the murders were still unsolved. No one had been identified as the triggerman. As long as that riddle remained unsolved, it would remain an open case for the Sherry children. Unfortunately, the case seemed likely to remain open, barring any new information coming to light from a credible source. It seemed very likely that the case would never be solved, despite statements by U.S. Attorney George Phillips that the investigation would continue until the murderer was found.

A month after their sentencing for the Lonely Hearts conspiracy, Nix, Gillich, and Lenny Swetman were found guilty of trafficking in marijuana in a separate trial. Five more years were added to Nix and Gillich’s sentences, and Swetman received five years, as well.

Kirksey McCord Nix—the Dixie Mafia kingpin at Angola who ordered the hits—as well as the hit man who killed the Sherrys each received life sentences. (Murder and the Dixie Mafia, Federal Bureau of Investigation)

The next stage was the consideration of the defendants’ appeals. The appeals went to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans in 1993. Despite the impassioned pleas of defense lawyers, some challenging the constitutionality of the verdict and proceedings, the sentences were all upheld. An appeal was then made to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the justices there declined to hear the case.

That same year, Pete Halat came up for re-election. Halat lost his bid for re-election to Republican candidate A.J. Holloway by a mere 14 votes.

It was believed that Halat was involved in the Murder Plot and the Lonely Hearts scam. So, the investigation continued.

In July 1992, Agent Bell got the break he was waiting for.

Mike Gillich was desperate to find a way out of prison. He contacted one of his associates in Biloxi and asked him to approach Robbie Gant with an offer. Gant told Agent Bell about it.

The associate had offered Robbie Gant $20,000 to recant his testimony against Gillich and sign a false affidavit stating that he had been threatened by Agent Bell to testify falsely against Gillich. Gant agreed to wear a wire and get the accomplice’s offer on tape. Gant accepted the bribe as instructed.

By 1993, six years after the double murder of Margaret and Vince Sherry, there had been no murder conviction, and Pete Halat was still free and running the City of Biloxi.

The year before, Mayor Halat had broken ground on the city’s first big casino. The press still hounded him about his involvement in the Sherry murders. He remained adamant about his innocence.

In October 1993, Mike Gillich finally decided to cooperate after being hit with bribery charges. He would tell the story from an insider’s point of view. Gillich did not want to accrue more jail time, so he cut a deal before the bribery trial began. The Dixie Mafia member told what he knew about the murders. As a career criminal, Gillich initially tried to bluff his way out. His deception did not work, leaving him with no alternative. Gillich knew all the details.

When Nix was looking for an attorney, Gillich introduced him to Pete Halat.

Then in 1994, Mike Gillich agreed to talk to the FBI in exchange for a shorter sentence. He said Pete Halat told Kirksey Nix that Vincent Sherry stole the money in order to save his own life. That’s when Nix and Gillich ordered a hit on Vincent. Nix and Gillich said they would split the cost of the hitman. They were going to hire Ransom but decided on a man named Thomas Holcomb. Later, they said Halat did offer to help pay, but Gillich supposedly told him it was taken care of. Margaret Sherry’s murder was just a bonus and a precaution.

Mike Gillich Implicates Pete Halat in Conspiracy to Commit Murder

In the case of Mike Gillich, it had precisely that effect. Facing possibly the rest of his life in jail, by the mid-1990s, the once-formidable Dixie Don was ready to sing the tune many had been waiting nearly a decade to hear. He was ready to finger the murderer in exchange for a clemency deal, of course.

When, during interviews with the FBI, he finally revealed who pulled the trigger on the Sherrys, the revelation was a shocker. It turned out to be someone who had never, in all that time, been suspected or publicly linked to any part of the conspiracy. The actual killer was a shadowy Dixie Mafia hitman who had flown completely under investigators’ radar for nine years: an ex-con and part-time carnival worker from Texas named Thomas Leslie Holcomb. The driver of the getaway car, Gillich said, was an ex-cop named Glenn Cook. Most damning of all, Gillich also directly implicated Pete Halat.

To prove his story about Holcomb, Gillich brought investigators to an old house where, he said, Holcomb had test-fired the .22. Closer investigation revealed bullet holes in the floor right where Gillich had said the shots were fired. Holcomb was located and arrested, charged with murder.

The noose was now tightening around Halat, with Mr. Mike hauling in the rope. Gillich described the fatal Angola meeting at which Nix and Halat had been present and asserted that Halat did, in fact, finger Vince as the one responsible for the missing money. Soon after that, according to Gillich’s account, Halat returned to Biloxi, closed his office’s safe deposit box, and opened a new one with Vince’s name on it and a number similar to that of the previous box. This, Halat apparently hoped, would link Vince to the theft of the money in Nix’s eyes.

It was enough for the prosecutors to proceed. Halat was indicted on October 23, 1996. Along with Nix, Holcomb, and LaRa Sharpe, he was charged with conspiracy to commit murder. Of course, Halat, now a former mayor, vociferously denied the charges, but by this point, his credibility was shot.

In June 1997, nearly a decade after the Sherry murders, the trial of Halat and the others opened. The government’s case was similar to the one they presented six years earlier but with the added factor of Halat’s presence at the defense table, this time as a defendant, not as a witness for the defense. It may have been Halat’s worst nightmare come to pass when Gillich took the witness stand and swore, under oath, that Halat was up to his ears in both the lonelyhearts scam and the Sherry murders.

The second trial finally gave prosecutors the long-awaited opportunity to introduce key testimony that couldn’t be included earlier. It was Chuck Leger’s statement about Halat’s reaction to finding Vince’s body. Leger testified that Halat told him, “Vince and Margaret are dead,” even though Halat had only seen Vince’s body at that point. How could Halat have known both of them were dead if he hadn’t seen both bodies? He had to have known about the murder ahead of time.

This last revelation appeared to cook Halat’s goose. When the defense had their turn, the best they could do was call two witnesses whose total testimony time was under two hours. Following closing arguments, the jury deliberated for a week before reaching a verdict.

Halat was found guilty of lying and concealing records of Nix’s prison scam. The next day, he and the other defendants were found guilty of conspiring to commit murder. Several months later, sentences were passed. Life for Nix and Holcomb, five years for LaRa for obstruction of justice, and eighteen years for Halat.

In exchange for Mike Gillich’s testimony, Judge Pickering rewarded him with a sentence reduction. He was released from prison in July 2000 after serving nine years of his sentence.

Pete Halat was convicted in 1997 of conspiracy to commit racketeering, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and conspiracy to commit wire fraud. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

While sentencing Pete Halat, the Judge said if he had been truthful about the missing money in the beginning, Vincent and Margaret would not be dead.

Motive for the Murders

The missing money that led to the deaths of Vincent and Margaret Sherry has never been accounted for.

From prison, Nix was running a scam on gay men – hoping to get enough money to bribe his way out of jail; a scam ran out of Halat’s law office after Vincent Sherry was appointed Circuit Judge in 1986.

Two significant discoveries emerged as the investigation proceeded: The mastermind behind this con game was a convicted murderer in Angola named Kirksey McCord Nix Jr., and the primary receiver of the ill-gotten monies was the Biloxi law firm of Halat & Sherry.

One of the ways Vince Sherry earned his money was by being on the receiving end of the funds Nix was raking in on his Lonely Hearts scam from Angola Prison. Vince Sherry was often the one who banked the money for Nix.

Halat blamed Sherry when some of Nix’s money came up missing. Nix believed him and ordered the hit.

In a WLOX News exclusive, Pete Halat said despite what people may think, he had no role in the 1987 murders of Vincent and Margaret Sherry.

“I can tell you that there isn’t a word in the English language that I’m not intelligent enough to know,” the former Biloxi mayor said, “that can more strongly deny that I was ever involved in anything to do with Vince and Margaret being hurt, and Vince and Margaret being killed.”

Halat’s comments about the Sherry murders and his 15 years and nine months in federal prison came during a candid, one-hour interview conducted by WLOX News Director Brad Kessie. That interview recounted details from a 1997 trial when Halat was found guilty of conspiracy to violate the racketeering statute, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

The guilty verdicts focused on a Lonely Hearts scam run out of the Angola prison by some of Halat’s clients.

The Sherry murders grew out of Kirksey Nix’s Lonely Hearts scam. A few months before their death, Halat had closed the safe deposit box that he and Nix’s girlfriend had access to, effectively cutting off her access to the money. He then transferred the money to a box that only he and Judge Sherry could use. Motivated by greed, Pete Halat stole $100,000. As Nix’s trusted accomplice, Halat blamed Judge Sherry for the theft. In late 1996, Halat went to Gillich with news of the theft, stating that much of the money was missing. Halat knew that Kirksey Nix would be very furious about this.

It was not known who ordered Margaret’s death; however, she posed a threat to the criminal organizations. With Margaret dead, Halat would be free to run the town.

Gillich said that he and Halat planned the murders. Ransom and Rhodes provided the murder weapon. When they passed on doing the hit, Gillich found a replacement, a Texas-based criminal known as Thomas Holcombe. He would be paid $20,000. Gillich helped provide the car with the help of locksmith Swetman.

In October 1996, agents arrested hitman Thomas Holcombe.

Kirksey Nix was also tried and convicted.

Nix’s girlfriend, LaRa Sharpe, got 5 years for her involvement.

Margaret and Vince Sherry’s murderers were finally brought to justice.

After an investigation that stretched out to more than a decade, it turns out a Dixie Mafia kingpin and his local associates plotted the murders. Vincent Sherry and his wife were killed in their Biloxi home in a murder-for-hire plot that involved hundreds of thousands of dollars in missing funds from a prison-based money scam. Cook admitted delivering $20,000 to a Texas hitman for killing the couple.

It took the persistence of Lynne Sposito, the Sherry’s oldest daughter, and now retired FBI agent Keith Bell to come up with the arrests and convictions of Dixie Mafia kingpin Kirksey McCord Nix, already serving a life sentence at Angola state prison in Louisiana and strip club owner, Mike Gillich.

Ex-Biloxi Mayor Still Denies Role in Killings (The Mississippi Link)

Former Biloxi Mayor Pete Halat, now free from prison, still says he had no part in a murder plot that led to him spending almost 16 years in federal prison.

Halat told WLOX-TV that he had “absolutely nothing” to do with the murders of Harrison County Circuit Judge Vincent Sherry and his wife, Margaret, in 1987.

Vincent Sherry and Pete Halat had been law partners since 1981. Vincent Sherry was appointed Circuit Court Judge in 1986. Pete Halat was elected Mayor in 1989, losing a re-election bid in 1993.

Halat was convicted in 1997 of conspiracy to commit racketeering, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and conspiracy to commit wire fraud. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

According to court testimony, Pete Halat knew about the murder plot against Margaret and Vincent Sherry and failed to notify law enforcement.

A Lucrative Money Scam. Embezzlement. Murder For Hire Plot. Did the Conspirators Believe They Could Get Away with the Double Killing of Judge Vincent Sherry and His Wife?

Background on The Dixie Mafia’s Murder-For-Hire Conspiracy

It turned out that the local gangsters, known as the Dixie Mafia, had been running a scam where they targeted gay men in an extortion sting. Pretending to young gay men and then blackmailing anyone who responded, demanding large sums of cash. They gave this cash to their lawyer, Pete Halat, for safekeeping, but he spent the cash. When it came time to hand it over, he told them his former partner Vincent Sherry had taken it.

Fabian landed in Angola for the kidnapping and murder of a state trooper. There, he buddied up with his fellow Dixie Mafia compadre, Kirksey Nix. Among other things, they worked together on the Lonely Hearts scams. Then there was an argument, most likely over money, and Fabian threatened to start running his own con game. But, even more than that, Fabian, serving a long sentence, was looking for an out. That’s when he decided to sing.

Two years earlier, a large chunk of the money Nix had been laundering through the Halat & Sherry firm was missing. About $500,000 worth, by Fabian’s account, though later sources put the amount closer to $200,000. A meeting was held at Angola between Nix and Halat and several other inmates; among them was Bobby Joe Fabian. When Nix asked Halat about the missing money, Halat denied any responsibility and blamed it on Vince Sherry. A hit was then ordered on Vince, and a career killer named John Ransom was contracted to do the dirty work.

Fabian also told Armistead that he didn’t believe Vince took the money and, instead, blamed Halat. And possibly LaRa, as well. The day after meeting with Armistead, Fabian called Lynne and repeated the same information about the contract hit on Vince. That was as much as Fabian could offer, but it was enough to move the investigation forward in a specific direction.

Two years after the Sherry Murders, Kirksey Nix continued to run his Lonely Hearts scam from jail, and its profitability kept growing.

Although no exact figures could be determined, his earnings were estimated to have been hundreds of thousands of dollars. With each check deposited in his bank accounts, his dream of buying his freedom seemed to get closer to reality. And, despite significant dissension within his intricate network of collaborators, his operations went on largely unimpeded. Gay men being bilked out of their money were reluctant to embarrass themselves by going to authorities if they suspected the fraud and did not elicit much sympathy from those who were in on or aware of the scam.

In 1989, reporter Ed Bryson traveled to the Louisiana State Prison at Angola. He talked with Bobby Joe Fabian, an inmate who claimed the murders were the result of a scam Fabian had been running with fellow inmate Kirksey McCord Nix.

Fabian told Ed and the investigators that the money from their scam was funneled through Pete Halat’s law office. Halat shared that office with Judge Sherry. When some of the money disappeared, Fabian said Halat blamed Sherry, so Nix wanted Judge Sherry punished.

“The Sherrys were killed because a hit was put on them by Kirksey Nix,” Fabian told WLBT during the interview. He also provided other details about how the murders were planned and carried out. There were other conspirators, including Thomas Leslie Holcomb, a hitman out of Texas, convicted of pulling the trigger on the Sherrys.

By the summer of 1989, the Harrison County Sheriff’s Office was still guarding the secret of Fabian’s complicity in the investigation and keeping it out of the hands of the Biloxi Police Department. This was done to keep them from tipping off Halat who had been just sworn in as Mayor and to whom they now owed their jobs. Then, later in July of that year, Cook received word from authorities in Georgia that Ransom and another accomplice had been arrested on a murder charge. The weapon used in this murder was similar to the one used on the Sherrys.

With Ransom safely in custody, Cook ordered a search of his house. What was found were silencers, a roll of foam of the type normally used in silencers, an address book with LaRa’s phone number in it, and a phony stock certificate from a scam Ransom and Nix concocted drawn up by the Halat & Sherry firm. A connection between Ransom and the other suspects in the murder-for-hire plot appeared to be conclusively established. The pieces were finally being fitted into place.

Word spread that a convict in Angola had been responsible for tipping off investigators, and Fabian began fearing for his life. Prison snitches were reviled above nearly all other offenses among inmates, and Fabian’s fears were very real ones. He begged for protective measures and received them, but not before going on record officially and spilling the beans during a live interview with a TV reporter. Among other things, Fabian, with his features electronically smudged, implicated Halat in the conspiracy to kill the Sherrys.

“Peter Halat knew that somebody was gonna die, and better Sherry than him,” Fabian said on camera.

Immediately, Halat was besieged with requests by the media to comment on the allegations, and during a press conference the following day, he vehemently denied any involvement.

But, despite his best denials, Halat could not put the story to rest. It had become too hot by that point.

“I had nothing to do with that. Absolutely nothing,” Halat told WLOX. “If I would have had anything to do with it, if I would have known anything about it, I would have done everything in my power to prevent it.”

Other details of the case spilled out: the scam money arriving in Halat’s law office, the role played by LaRa Sharpe, the enormous number of phone calls to and from Angola Prison, and more. Halat knew he had to fight back, and he did.

Five days after his first press conference, he called another, this time producing visitor logs from Angola that appeared to disprove Fabian’s allegations. No records showed a meeting in March — or any other month — in 1987, the time frame pinpointed by Fabian when the murder conspiracy was supposed to have been hatched. However, only a handful of people — four investigators plus Lynne — knew about the March 1987 meeting. Fabian had divulged it to only them and had never mentioned it in his televised interview. Halat’s determined efforts to distance himself from that place and time only fueled suspicion among those in the know. How could he have known Fabian was referring to a meeting in March 1987 unless he had actually been there?

The prison visitation logs also showed a small detail that no one in the media picked up on immediately: an attempt by Halat to bring Gillich into the prison with him, with Gillich posing as a private investigator. Lacking the proper credentials, Gillich had been turned away, but the notation in the logs had great significance. It was the first time Gillich’s name had publicly surfaced in possible connection with the scams and the murder conspiracy.

Soon after Halat’s very public denials, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi George Phillips made an announcement. His office, along with the FBI, was joining the investigation, and a grand jury was being convened in Jackson to look into the case. Subpoenas were to be issued. Finally, nearly two years after Vince and Margaret Sherry had been murdered, the FBI was getting officially involved.

As more details in the Sherry murder investigation were publicly aired, more blanks were filled in. Several key pieces of information came from an unexpected source: someone who had had that information all along but hadn’t realized the significance of it.

Charles “Chuck” Leger was the young attorney Halat had chosen to replace Vince in the firm when Vince had been elevated to the Circuit Court bench. A day or two before the Sherrys’ murder, Leger told investigators in August 1989 that a tall, lanky man with a limp in his right leg had come up to him in downtown Biloxi asking where he might find Vincent Sherry. Not seeing anything amiss in the request for information but being somewhat spooked by the man’s appearance, Leger replied that Vince was probably at the courthouse and watched as the man limped off. When the face of that particular man was shown on TV in connection with the Sherry murders, Leger recognized it. It was the face of John Ransom.

A second key detail provided by Leger centered on Halat’s initial reaction to the discovery of the Sherrys’ bodies and his choice of words at that time. When Vince and Margaret hadn’t been seen for a few days, Halat drove out to the Sherry’s’ house accompanied by Leger. The two of them entered the house through the front door, which was unlocked. When Halat gave his first statement to investigators, he told them that immediately after seeing Vince lying dead on the floor, he retreated out of the house without looking further. “I had no idea that Mrs. Sherry was in the house,” he told crime scene investigators.

However, according to Leger, while they were in the house, Halat ushered him outside quickly, saying, “Vince and Margaret are dead.” How could he have known that if he hadn’t gone into the bedroom and seen Margaret’s body?

Around the same time Leger was relating his story to investigators, another piece of the puzzle slipped into place. By this point, the investigation had added a new face to those looking for more clues to the double slaying: FBI Special Agent Keith Bell. His expertise and experience gave the investigation a much-needed boost, and he would later play an even more pivotal role.

In October 1989, Bell received a call from an FBI agent in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The agent told Bell another potential witness had secretly come forward: a convicted armed robber and recovering heroin addict named Robert Hallal. He had served twelve years of a fifty-year sentence at Angola and was involved with Nix’s Lonely Hearts scam. Upon his parole in May 1987, Hallal claimed he had been offered a job upon release: kill a judge in Biloxi.

Bell and the Baton Rouge agent met with Hallal in St. Francisville, La., twenty miles from Angola, to preserve the secrecy of the meeting. Accompanied by guards from the prison, where he had been returned following a conviction and 95-year sentence for armed robbery, Hallal related his story to the two agents.

Hallal said he had been the voice of many characters on the prison phone during the scam, and he also helped line up “road dogs” (runners) to pick up and deliver scam money. Hallal’s ex-wife, Patricia, also had a role in this end of the operation. As a reward for her complicity, Hallal told the agents Mike Gillich had given her money to set up an X-rated video store in Mobile, Ala., where she also worked as a prostitute.

In July 1987, Nix called him, and, according to Humes’ account of the conversation, Nix said, “I’d like for you to knock someone off for me. You know who my man is on the Gulf Coast, right? Go see Mr. Mike if you’re interested.”

Continuing his account for the agents, Hallal said he delivered an $11,000 payment for Nix to Gillich and received the details of the planned hit. Sherry’s name wasn’t mentioned, but Hallal had balked at the suggestion of killing someone as publicly prominent as a judge. Gillich had allegedly insisted, telling Hallal that the job wouldn’t be a problem “because someone from Georgia will mail you a pistol with a silencer.” Although the conversation had ended with Hallal’s continued refusal to do the job, the two agents concluded he was talking about John Ransom, who was from Georgia. The revelation placed Gillich squarely in the thick conspiracy to kill the Sherrys.

Even as pieces of the puzzle fell ever more neatly into place. An air-tight case would have to be built — one strong enough to convince a grand jury to hand down an indictment — and it would not be easy getting an indictment against a sitting mayor, mainly relying on testimony from convicted felons trying to cut deals with the state. As First Assistant U.S. Attorney Kent McDaniel told Lynne Sposito, “We only get one shot at it.”

All the while, Lynne had been continuing to get death threats, and, in those days before caller ID, she had no way of knowing from where the calls were coming. But the grand jury had been impaneled, and witnesses were being subpoenaed to appear before it. It wouldn’t be much longer before they would decide whether or not the case had enough merit to go forward, whether or not they could hand down any indictments before their mandate expired—the clock was ticking. The U.S. Attorney had only until the end of May 1991 to ask the grand jury for an indictment, and the deadline was fast approaching. Moreover, the five-year statute of limitations on many scam charges was looming. If no indictments were made there, the scam would be much less helpful as evidence in any later trial, thus making a conviction in the Sherry murder case less likely. Action had to be taken soon.

However, before the grand jury could be presented with an indictment request, they had one more witness to interrogate: Pete Halat. His two-and-a-half-hour testimony yielded nothing anyone could use against him or any of the principals involved, but it was a necessary step, nonetheless.

On May 15, 1991, Cook and Bell drove to Jackson to present their investigation summary to the grand jury. Later that day, the grand jury handed down the indictment nearly four years in the making.

The charges were one count related to the illegal scam and murder conspiracy, another count of wire fraud, and two counts of traveling across state lines with the intent of committing murder-for-hire. Kirksey McCord Nix, Mike Gillich, John Ransom, and LaRa Sharpe were named in the indictment. Not named was Pete Halat. He would, however, remain under suspicion as an unindicted conspirator subject to a continuing investigation. He was off the hook for the moment but could be indicted later if evidence surfaced that prosecutors felt they could take to trial.

Halat wasted no time trying to clear his name and reputation. After the indictment was unsealed on May 21, 1991, he called a press conference proclaiming his vindication. In his customary pugnacious demeanor when dealing with the media, he criticized the press for relating “a preposterous and pathetic story” told by a “lying thug.” He continued to deny any involvement in Nix’s prison scams or in the murders of the Sherrys, whom he continued to refer to as his friends. Halat also announced that he planned to run for re-election in 1993.

Gillich was not about to go down easy. Nicknamed “The Dixie Don,” he seemed determined to live up to his tough reputation. He also, befitting a man with money, hired the best lawyers. He continued to publicly deny any involvement in the deaths of the Sherrys, even though the indictment never specifically named a triggerman.

The case stayed in the headlines throughout the summer, with rampant speculation on the outcome. Lists of witnesses for both sides were filed with the court, and lawyers prepared the arguments they would make in court. When the trial finally convened, the prosecution and the defense were fully ready.

More Information on the Murder Plot and the Dixie Mafia

The FBI Files: The Dixie Mafia—Season 2, Episode 7 (YouTube Video)

The Dixie Mafia: Corruption and Murder in Biloxi, Mississippi (The Crime Wire)

Biloxi’s Tale of Murder, Extortion and Racy Photos (The New York Times)

The Little-Known Story of the Dixie Mafia: The ‘Cornbread Cosa Nostra’ of the South

Biloxi Confidential: The Dixie Mafia (Crime Library)

On October 23, 1996, Halat was indicted on federal charges related to his involvement in the 1987 murders of Vincent and Margaret Sherry. At the time the FBI believed that the two were killed on Halat’s orders after he thought that Judge Sherry was stealing from a bank account Halat kept for an imprisoned client, which held funds from Kirksey Nix’s Lonely Hearts scam.

It would later turn out however, that Vincent Sherry had never stolen money from Kirksey Nix’s dating scam and that it was in fact Pete Halat himself who had stolen $100,000 or more from the Lonely Hearts scam.

When Nix was enraged over noticing the amount of missing money and arranged for Pete Halat to visit him in prison and demanded an explanation from him, Halat quickly blamed Judge Sherry for the theft of the illicit funds and the two quietly agreed to have Judge Sherry and his wife murdered.

Shortly thereafter, Kirksey Nix ordered the deaths of Vincent and Margaret Sherry for the alleged theft of his money, and the Dixie Mafia’s leader on the streets, Mike Gillich, hired a hitman from Texas named Thomas Holcomb to commit the two murders. Thomas Leslie Holcomb was given the handgun with a homemade silencer which he used in the killings by Kirksey Nix’s girlfriend Sheri LaRa Sharpe, who in turn had received the gun from an enforcer for the Dixie Mafia named John Ransom who told her to give the gun to Holcomb for the hit on Mr. and Mrs. Sherry.

Halat was later convicted in 1997 of conspiracy to commit racketeering, obstruction of justice, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Halat was released in 2013 after 15 years, 9 months and 7 days in jail at the age of 70. He then worked as a handyman at a church in Hattiesburg the remainder of the year.

Mississippi Mud: Southern Justice and the Dixie Mafia by Edward Humes

UPDATED WITH EXPLOSIVE COURTROOM DETAILS. . . The riveting true-crime account of the heartbreaking murder that shook a Southern city to its corrupt foundation.

BILOXI, MISSISSIPPI: After the fatal shooting of one of the city’s most prominent couples—Vincent Sherry was a circuit court judge; his wife, Margaret, was running for mayor—their grief-stricken daughter came home to uncover the truth behind the crime that shocked a community and to follow leads that police seemed unable or unwilling to pursue. What Lynne Sposito soon discovered were bizarre connections to the Dixie Mafia, a predatory band of criminals who ran The Strip, Biloxi’s beachfront hub of sex, drugs, and sleaze. Armed with a savvy private eye—and a .357 Magnum—Lynne bravely entered a teeming underworld of merciless killers, ruthless con men, and venal politicians in order to bring her parents’ assassins to justice.

An Interesting Read: The Boys from Biloxi: A Legal Thriller by John Grisham

For most of the last hundred years, Biloxi was known for its beaches, resorts, and seafood industry. But it had a darker side. It was also notorious for corruption and vice, everything from gambling, prostitution, bootleg liquor, and drugs to contract killings. The vice was controlled by small cabal of mobsters, many of them rumored to be members of the Dixie Mafia. Life itself hangs in the balance in The Boys from Biloxi, a sweeping saga rich with history and with a large cast of unforgettable characters.

Biloxi Murder Conspiracy: A High-Stakes Crime

- Backpacking, Hiking, and Camping Safety Guides

- Kamala Harris Plan to Support Small Business Owners and Entrepreneurs

- Email Marketing Campaigns for Small Business Owners

- How to Create an Ergonomic Workspace at Home or Work

- Significant Takeaways from the Historic 2024 Presidential Debate

- How Pennsylvania is Supporting Kamala Harris for President

- How VIRGINIA is Supporting Kamala Harris for President

- How NORTH CAROLINA is Supporting Kamala Harris for President

- Ways to Pay It Forward and Change Lives

- Balancing Success: Practical Self-Care Strategies for Entrepreneurs

- Highlights from Kamala Harris Arizona Presidential Campaign

- Highlights from Kamala Harris South Georgia Presidential Campaign

- Highlights from Kamala Harris Wisconsin Presidential Campaign

- Highlights from Kamala Harris Nevada Presidential Campaign

- Highlights from Kamala Harris Michigan Presidential Campaigns

- How OHIO is Supporting Kamala Harris for President

- How ILLINOIS is Supporting Kamala Harris for President

- Kamala Harris Pennsylvania Bus Tour and Campaign Rally

- Kamala Harris Presidential Campaign Rally at Georgia State University

- Guides to Backpacking, Mountain Biking and Hiking Georgia

- Kamala Harris Raleigh North Carolina Presidential Campaign

- Moving and Relocating to Atlanta: How to Find Your New Home

- Money Matters: Insider Tips to Buying a Home

- Renting vs Owning a Home

- 3 Powerful Benefits of Using Managed WordPress Web Hosting

- Ways to Build Positive Credit

- Do It Yourself Credit Improvement Process

- A Trail of Clues to the Murder of Nicole Brown Simpson

- How Centra Tech’s Bitcoin Cryptocurrency Scheme Was Hatched and Discovered

- Starting a New Business as a New Mother: Tips for Thriving

- Guides to Backpacking and Hiking the Carolinas

- Guides to Hiking New York State and New Jersey

- Guides to Backpacking and Hiking Canada

- Guides to Hiking California and Nevada

- The Tragic Murder of Rebecca Postle Bliefnick

- How a Grad Student Murder Spotlights Female Joggers’ Safety Concerns

- How Massive Commercial Financial Fraud Was Discovered in Singapore

- Guide to Martha Stewart’s Hugely Successful Concept and Art of Presentation

- Did Billy Ray Turner Conspire with Sherra Wright to Kill Former NBA Player Lorenzen Wright?

- How Operation Rebound’s 7-Year Cold Case was Finally Solved

- Stylish Outdoor Fire Pits and Patio Heaters

- Mastering DIY Marketing: Essential Skills and Strategies for Small Business Owners

- Great Deals on Snug UGG All-Season Boots

- How a GeoLocation Expert Tracked a Killer

- Transgender Law Enforcement Officer Denied Medical Coverage for Gender Dysphoria

- How Video Surveillance Cameras Helped Identify and Track a Killer

- How Investigators Solved the Murder Mystery of Army Sergeant Tyrone Hassel III

- How a Love Obsession Led to the Brutal Murder of Anna Lisa Raymundo

- How Stephen Grant Tried to Get Away with Killing His Wife

- How Unrelenting Catfish Schemes Led to Fatal Suicide

- How Pain Clinic Owners Turned Patients’ Pain into Enormous Profits

- How to Recognize a Pain Pill Mill in Your Community

- How Authorities Have Shuttered Georgia Pain Clinics Massive Pain Pill Distributions

- How Pain Doctors Massive Opioid Prescriptions Lead to Pain Pill Overdose Deaths

- How Authorities Are Dismantling Pennsylvania Pain Clinics Prescribing Excessive Amounts of Opioid Pain Pills

- How Authorities Are Dismantling Alabama Pain Clinics Pain Pill Schemes

- How the Gilgo Beach Homicide Investigation Has Progressed

- How NYC Architect was Linked to Three Women’s Remains Found on Gilgo Beach

- How Investigators Discovered a Serial Killer Hiding in Plain Sight

- How Police Discovered the Concealed Murders of the Chen Family

- How a Vicious Child Custody Battle Led to the Murder of Christine Belford

- How Authorities Finally Captured a Serial Killer in Southern Louisiana

- How Authorities Are Busting Pill Mills in The Carolinas

- Unsolved Mystery: Triple Murder at the Blue Ridge Savings Bank

- How Montgomery County Police Quickly Unraveled the Murder of a Retail Store Employee in Bethesda

- How a Child Rapist and Murderer Almost Got Away with His Crimes in England

- How Authorities Are Dismantling Pill Mills in the United States

- How Federal Agencies Are Dismantling Michigan Pain Clinic Doctors Scheme to Distribute Enormous Amounts of Opioid Pain Pills

- How Authorities Are Cracking Down on Virginia Pain Clinics Massive Pain Pill Operations

- How Authorities Are Honing in on Kentucky Pain Clinics Distributing Opioid Painkiller Pills for Profit

- How Federal Agencies Are Shutting Down Maryland Pain Clinics Operating as Pill Mills

- How Federal Agencies Are Dismantling New York Pain Clinics Vast Pain Pill Operations

- How the Senseless Murder of Tequila Suter Was Quickly Solved

- How Authorities Are Dismantling Ohio Pain Clinics Prescribing Excessive Pain Pills

- How Authorities are Dismantling Tennessee Pain Clinics Prescribing Massive Quantities of Opioid Pain Pills